What is the Gut Microbiome

From birth, your body becomes home to a vast, invisible population—trillions of microbial residents that help regulate digestion, immunity, metabolism, and even mood [1]. This ecosystem is called the gut microbiome and it’s one of the most vital contributors to your long-term well-being.

Until recently, bacteria were mostly seen as enemies, largely associated with germs. But thanks to advances in gene sequencing, we now know better. Most of them are not intruders. They’re your inner allies, many of which you couldn’t live without.

Far more than passengers, these microbes form a highly structured, co-evolved community.

They’ve evolved alongside us for millennia, learning to interact with our bodies in ways that shape health, resilience, and adaptation. They respond to what you eat, how you live, and even how you feel. And in return, they help shape nearly every system in your body—from digestion to brain function.

Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron is one of your gut’s most industrious residents. It encodes 260 enzymes to help digest complex carbohydrates, nearly triple what human genes can manage on their own.

You're Not Alone in There

Your gut is home to a complex ecosystem that is unique to you, comprising approximately 2,000 bacterial species [2]. These are classified into broad taxonomic groups called phyla. Among them, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes dominate, making up roughly 90% of the gut microbiota [3]. Other important groups include Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Fusobacteria, and Verrucomicrobia.

While your human genome contains around 23,000 genes, your gut microbes bring over 3 million, forming what’s known as your second genome [4]. Together, these genes produce thousands of compounds, e.g. enzymes, vitamins, metabolites, many of which your own body can’t produce.

For example, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, a common gut bacterium, encodes 260 carbohydrate-digesting enzymes, compared to just 97 encoded by human genes [5].

What Does the Gut Microbiome Do?

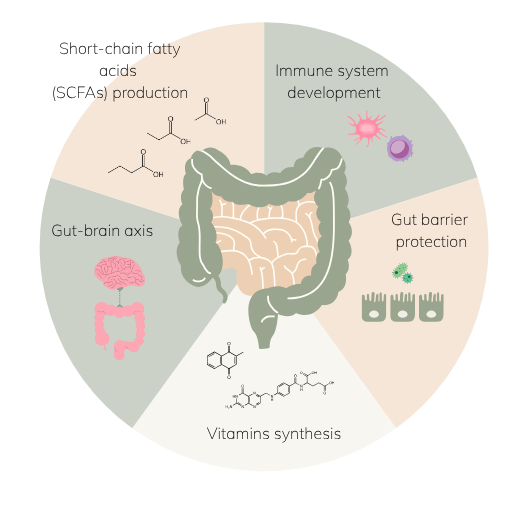

- Digestive Support: Breaks down dietary fiber and resistant starch into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, acetate, and propionate, compounds that regulate energy, glucose, lipid metabolism, and even immune function [6].

- Immune Training: Roughly 70–80% of your immune system resides in the gut. Microbes interact with it continuously [7], modulating immune cell development, T cell differentiation, and inflammatory signaling [8].

- Barrier Protection: A healthy microbiome reinforces the gut lining [9]. Butyrate, for example, promotes tight-junction assembly and mucin synthesis, fortifying your defense against harmful invaders [10]. This internal barrier strength can echo outward, supporting the skin’s own protective barrier by reducing systemic inflammation and helping maintain hydration from within.

- Vitamin Synthesis: Your gut microbes help produce key nutrients your body can’t make, including vitamin B12 [11], folate [12], vitamin K, riboflavin, biotin, nicotinic acid, pantothenic acid, pyridoxine and thiamine [13].

- Mood & Brain Function: Your gut and brain are in constant dialogue via the gut-brain axis. Some microbes produce neurotransmitters like serotonin and GABA, influencing mood, focus, and emotional well-being [14].

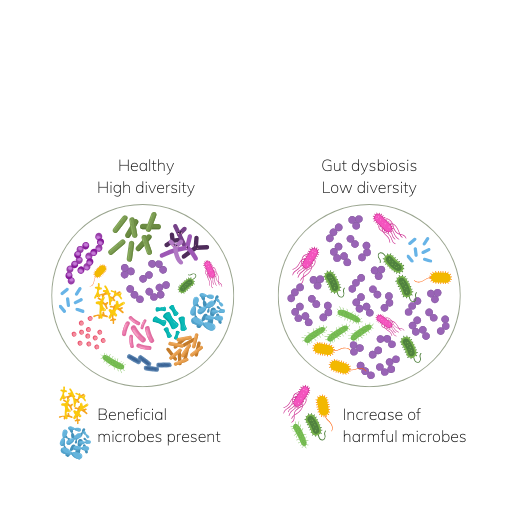

Gut dysbiosis is commonly defined as a decrease in microbial diversity, a decrease of beneficial microbes and an increase potentially harmful microorganisms [15].

The Forest Within: A Lesson in Diversity

So, how do these functions come together?

Thousands of species, trillions of microbes—living together in delicate harmony.

Think of your gut as a forest: layered, diverse, and alive with interaction. In a healthy forest, biodiversity creates resilience. Your microbiome is no different.

Microbiota diversity is a measure how many species exist and how evenly they’re distributed. It is one of the common indicators of gut health. Rich diversity provides functional redundancy, helping your microbiome withstand disruptions, e.g. stress, diet changes, and pathogens.

Low diversity, on the other hand, is one of the hallmarks of dysbiosis. It’s been linked to autoimmune diseases, obesity, metabolic dysfunction, and age-related decline [4].

Enterotypes: Microbial Signatures That Reflect Your Diet

While no two microbiomes are identical, scientists have identified enterotypes, distinct clusters of gut communities shaped by diet and lifestyle [16]:

- Enterotype I – Bacteroides-dominant

Common in industrialized populations; associated with high-fat, low-fiber diets. - Enterotype II – Prevotella-dominant

More common in traditional, plant-rich diets; efficient fiber fermenters with higher SCFA output. - Enterotype III – Ruminococcus and Akkermansia

Often overlapping with Enterotype I; but involved in mucin degradation and gut lining interactions.

These patterns aren’t fixed like blood types—they’re malleable, especially through diet and lifestyle. Still, once stable, your microbiome tends to hold its shape unless significantly disrupted (e.g. by antibiotics).

Why Should You Care?

Because this evolution-long partnership is under pressure.

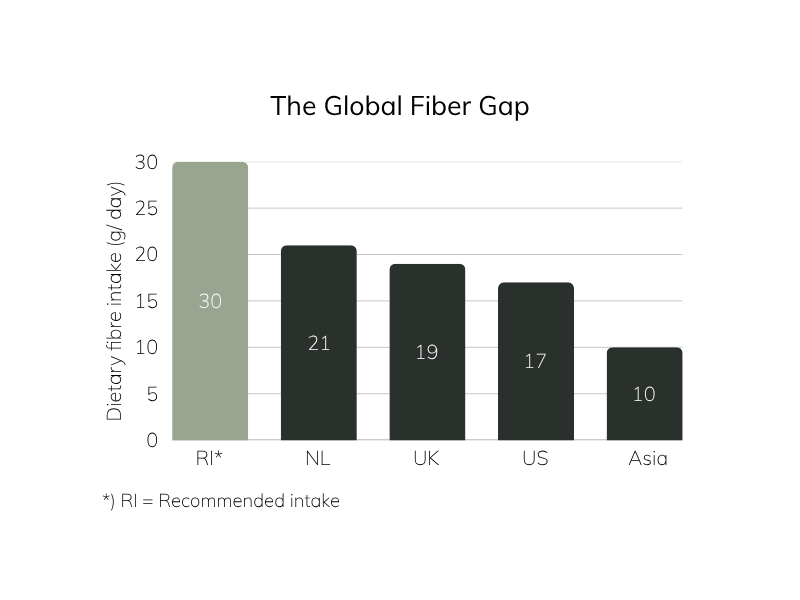

Our modern life is a perfect storm of antibiotics, processed foods, sedentary habits, stress, and environmental pollutants, and it has disrupted our gut microbiota balance. Particularly in our modern diet, we unintentionally deplete our beneficial gut microbes of their fuel: dietary fiber. Prehistoric humans are estimated to have consumed over 100 grams of fiber daily from wild plants and tubers [17]. Modern populations consume just 10–21 grams [18–20].

Virtually all diet-related chronic diseases have been linked to the microbiome [21]. Dysbiosis, specifically, is linked to a growing list of chronic conditions: cardiovascular disease (CVD) [22], diabetes [23], colorectal cancer (CRC) [24], and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [25].

Therefore, caring for your gut microbiome is no longer niche, it’s foundational. And the good news? It’s never too late to start.

How to Support Your Gut Microbiome

- Nourish – Feed your microbes. Diverse fiber fuels good bacteria and leads to SCFA production, essential for gut lining and immune support. Also add fermented foods like yogurt, kefir, kimchi and sauerkraut.

- Move – Physical activity increases microbial diversity and motility [26], supporting regularity and reducing bloating.

- Balance – Cut the noise. Excess sugar, alcohol, ultra-processed food, and chronic stress all impair microbiome health.

- Restore – Prioritize rest, hydration, and gut-soothing nutrients like L-glutamine. Consider supplements, e.g. prebiotics and probiotics targeted to repair and rebuild.

- Reset – Let your gut breathe. Mindful eating, time-restricted feeding, and gentle fasting gives the gut time to reset and reduce inflammation.

Start With the Basics

At AB INTRA, we believe in working with your biology, not against it.

Our Gutbiotica line is formulated to nourish your microbiome gently, deeply, and sustainably. Whether you’re starting fresh or refining your routine, these science-backed blends support a resilient gut from the inside out.

Because health isn’t just something you build—

It’s something you take care of.

References

- S. R. Gill et al., “Metagenomic Analysis of the Human Distal Gut Microbiome,” Science (80-. )., vol. 312, no. 5778, pp. 1355–1359, Jun. 2006, doi: 10.1126/science.1124234.

- A. Almeida et al., “A new genomic blueprint of the human gut microbiota,” Nature, vol. 568, no. 7753, pp. 499–504, 2019, doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0965-1.

- M. Arumugam et al., “Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome,” Nature, vol. 473, no. 7346, pp. 174–180, 2011, doi: 10.1038/nature09944.

- A. M. Valdes, J. Walter, E. Segal, and T. D. Spector, “Role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health,” BMJ, vol. 361, p. k2179, Jun. 2018, doi: 10.1136/bmj.k2179.

- B. L. Cantarel, V. Lombard, and B. Henrissat, “Complex Carbohydrate Utilization by the Healthy Human Microbiome,” PLoS One, vol. 7, no. 6, p. e28742, Jun. 2012.

- P. D. Cani and B. F. Jordan, “Gut microbiota-mediated inflammation in obesity: a link with gastrointestinal cancer,” Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol., vol. 15, no. 11, pp. 671–682, 2018, doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0025-6.

- D. Zheng, T. Liwinski, and E. Elinav, “Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease,” Cell Res., vol. 30, no. 6, pp. 492–506, 2020, doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0332-7.

- S. A. Scott, J. Fu, and P. V Chang, “Microbial tryptophan metabolites regulate gut barrier function via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 117, no. 32, pp. 19376–19387, Aug. 2020, doi: 10.1073/pnas.2000047117.

- M. Régnier, M. Van Hul, C. Knauf, and P. D. Cani, “Gut microbiome, endocrine control of gut barrier function and metabolic diseases,” J. Endocrinol., vol. 248, no. 2, pp. R67–R82, 2021, doi: 10.1530/JOE-20-0473.

- D. J. Morrison and T. Preston, “Formation of short chain fatty acids by the gut microbiota and their impact on human metabolism,” Gut Microbes, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 189–200, May 2016, doi: 10.1080/19490976.2015.1134082.

- J. G. LeBlanc, C. Milani, G. S. de Giori, F. Sesma, D. van Sinderen, and M. Ventura, “Bacteria as vitamin suppliers to their host: a gut microbiota perspective,” Curr. Opin. Biotechnol., vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 160–168, 2013, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2012.08.005.

- P. Anna, C. Lisa, A. Alberto, Z. Simona, M. Diego, and R. Maddalena, “Folate Production by Bifidobacteria as a Potential Probiotic Property,” Appl. Environ. Microbiol., vol. 73, no. 1, pp. 179–185, Jan. 2007, doi: 10.1128/AEM.01763-06.

- M. J. Hill, “Intestinal flora and endogenous vitamin synthesis,” Eur. J. Cancer Prev., vol. 6, no. 2, 1997.

- J. F. Cryan et al., “The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis,” Physiol. Rev., vol. 99, no. 4, pp. 1877–2013, Aug. 2019, doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2018.

- C. Petersen and J. L. Round, “Defining dysbiosis and its influence on host immunity and disease,” Cell. Microbiol., vol. 16, no. 7, pp. 1024–1033, Jul. 2014, doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/cmi.12308.

- K. E. Hays, P. Jacob M., and R. and Ryznar, “The interplay between gut microbiota, short-chain fatty acids, and implications for host health and disease,” Gut Microbes, vol. 16, no. 1, p. 2393270, Dec. 2024, doi: 10.1080/19490976.2024.2393270.

- S. Jew, S. S. AbuMweis, and P. J. H. Jones, “Evolution of the Human Diet: Linking Our Ancestral Diet to Modern Functional Foods as a Means of Chronic Disease Prevention,” J. Med. Food, vol. 12, no. 5, pp. 925–934, Oct. 2009, doi: 10.1089/jmf.2008.0268.

- E. L. Sanderman-Nawijn, H. A. M. Brants, C. S. Dinnissen, M. C. Ocké, and C. T. M. van Rossum, “Energy and nutrient intake in the Netherlands. Results of the Dutch National Food Consumption Survey 2019-2021,” De inname van energie en voedingsstoffen in Nederland. Resultaten van de Nederlandse voedselconsumptiepeiling 2019-2021. Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu RIVM, 2024.

- Public Health England FSA, “National Diet and Nutrition Survey Results from Years 7 and 8 (combined) of the Rolling Programme (2014/2015 to 2015/2016),” 2018.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, “What We Eat in America, NHANES 2017–2018: Usual Nutrient Intakes from Food and Beverages, by Gender and Age,” 2020.

- I. Sekirov, S. L. Russell, L. C. M. Antunes, and B. B. Finlay, “Gut Microbiota in Health and Disease,” Physiol. Rev., vol. 90, no. 3, pp. 859–904, Jul. 2010, doi: 10.1152/physrev.00045.2009.

- F. H. Karlsson et al., “Symptomatic atherosclerosis is associated with an altered gut metagenome,” Nat. Commun., vol. 3, no. 1, p. 1245, 2012, doi: 10.1038/ncomms2266.

- C. Ceccarani et al., “Proteobacteria Overgrowth and Butyrate-Producing Taxa Depletion in the Gut Microbiota of Glycogen Storage Disease Type 1 Patients,” Metabolites, vol. 10, no. 4. 2020, doi: 10.3390/metabo10040133.

- X. Fan, Y. Jin, G. Chen, X. Ma, and L. Zhang, “Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis Drives the Development of Colorectal Cancer,” Digestion, vol. 102, no. 4, pp. 508–515, Sep. 2020, doi: 10.1159/000508328.

- D. N. Frank, A. L. St. Amand, R. A. Feldman, E. C. Boedeker, N. Harpaz, and N. R. Pace, “Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of microbial community imbalances in human inflammatory bowel diseases,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 104, no. 34, pp. 13780–13785, Aug. 2007, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706625104.

- R. Codella, L. Luzi, and I. Terruzzi, “Exercise has the guts: How physical activity may positively modulate gut microbiota in chronic and immune-based diseases,” Dig. Liver Dis., vol. 50, no. 4, pp. 331–341, 2018, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2017.11.016.

Next in Your Gut Health Journey

Explore further the fascinating world of gut health. Because better health is built one insight at a time.

Where Your Gut Meets Science

€ 269,85 Original price was: € 269,85.€ 214,95Current price is: € 214,95. incl. VAT

Consistency meets radiance. A 3-month supply of Skinbiotica COLLAGEN+—science-backed skin nutrition to support skin collagen, elasticity, and glow from within.

€ 209,90 Original price was: € 209,90.€ 179,95Current price is: € 179,95. incl. VAT

Complete beauty from within—Gutbiotica PRIME provides comprehensive microbiome support while Skinbiotica COLLAGEN+ promotes radiant and elastic skin.

€ 164,90 Original price was: € 164,90.€ 139,95Current price is: € 139,95. incl. VAT

A smart pairing for gut microbiome and weight support with Gutbiotica CORE and Fibersentials SHAPE to maintain a happy gut and support satiety naturally.